Actually, Western Icon Clint Eastwood Is Better Off When He’s Not a Cowboy

Though Westerns made him a legend, Clint Eastwood has much more to say about humanity and the modern world.

The mythology of the Western genre would be left unrealized if not for Clint Eastwood. The legendary actor-director, who remains active in the field into his 90s, serves as a one-two punch with John Wayne as the figure who shaped the iconography of the American frontier, with Eastwood more willing to expose a darker underbelly of the genre. He deconstructed the genre and the traditional cowboy protagonist with Westerns that spanned decades, from The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly, to ones which he also directed, including High Plains Drifter, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and Unforgiven. For as groundbreaking as he was in this genre, Eastwood was at his most refined, meditative, and creative when he stepped outside the Wild West. After making Westerns for decades across television and film, he utilized the layered and timeless themes of the genre in diverse settings. The combination of Western ideas in non-Western settings elevated him to his most interesting.

Eastwood as the Outlaw in ‘Dirty Harry’ and ‘Gran Torino’

The trait most associated with Westerns is the outlaw figure who rides into a new town and stirs up trouble with the locals. Eastwood has employed this character archetype in various non-Westerns as an actor, director, or both. The character who best fits this mold is a contemporary one: Harry Callahan of Dirty Harry. Despite being, on paper, the truest example of steadfast law enforcement and justice, “Dirty” Harry is more of an outlaw than The Man With No Name or Josey Wales. Beyond his embedded character traits, such as his combative relationship with his superior officers and boundary-pushing vigilantism, Callahan is an active comment on America in the 1970s. While the original 1971 Don Siegel film was criticized at the time for its fascist undertones, its anti-hero protagonist is emblematic of the kind of model law enforcer Americans desired, one that would shoot first and ask questions later amid a time when pure justice seemingly evaporated. The film’s transgressive nature is rooted in ’70s cinema sensibilities, where a police officer can carry the weight of an outlaw.

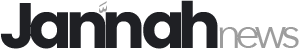

In a similarly provocative bid, Eastwood starred in and directed Gran Torino in 2008, a film that confronts his critiques of fascism and bigotry that he faced throughout his career. While the film can be viewed as overtly self-serving with Eastwood’s apologetic treatment of his own screen persona, his performance and direction lend enough pathos to set aside any glaring flaws of his characterization. In this film about a widowed Korean War veteran consumed by rage and bigotry, Walt Kowalski, Eastwood inverts the framework of a Western. Walt does not saddle up to a new town, but rather, the old neighborhood he’s lived in all his life has completely changed over. The film constructs the outlaw figure with entitled traditionalism. Walt, who was once fond of the white, working-class families that used to reside in the neighborhood, is bitter about the company of Hmong immigrants that have taken over the street. In the vain of John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards character in the John Ford classic, The Searchers, Walt is eventually determined to rescue a naive and ignorant local Hmong teen from the influence of the neighborhood gang. Despite showing signs of growth, Walt is no hero with his guidance over the teen. If anything, his self-created guardian angel complex is meant to fuel his repressed rage over the immigrants in the neighborhood.

Fatherhood and Masculinity in ‘A Perfect World’

Examination and deconstruction of masculinity are as important to Westerns as horses and revolvers. In one of the most subtle and meditative outputs of his filmography, Eastwood followed up his Best Picture-winning Unforgiven (and supposed career capstone) with A Perfect World. This film, following the journey of an escaped prison inmate, Butch Haynes (Kevin Costner), and the bond he forms with a kidnapped boy, Phillip (T.J. Lowther) is about empty fatherhood at its heart. For Butch, his only valve for channeling paternal care over the boy is through violence. He shows him how to point a gun, and invites him as an accomplice in numerous robberies in his plight to evade law enforcement, with the Texas Ranger in charge of the pursuit, Red Garnett, played by Eastwood. Butch and the boy have a spiritual kinship with each other, but violence and crime are the only way he can act as the surrogate father for a lonely child who, before taken hostage, lived a suppressed lifestyle restricted from an idealistic childhood. Eastwood, in a sobering manner, depicts someone who desires to teach a boy how to be a man through the usual antiquated tropes as a way to grapple with his lack of proper fatherhood. More exquisitely, Eastwood’s direction comments on the masculine archetype that he idealized throughout his career by shining a light on the emotional void that a man like Butch is filled with. Additionally, A Perfect World seamlessly weaves in quiet contemplation of law enforcement, with Eastwood’s character in over his head with the pursuit. The failure of the law is contextualized in relation to the profound relationship that Phillip has with Butch. The law could never comprehend the bond formed by these two lonely spirits drifting through time and space

Crime and Punishment in ‘Mystic River’

Since his early days in Hollywood, Eastwood’s fascination with crime and punishment has driven him to his greatest heights, particularly via Westerns. When these ideas are explored in a contemporary setting, such as in Mystic River, they combine for weighty emotional resonance. An ex-con, Jimmy Markum (Sean Penn), is distraught over the murder of his daughter. Because of the pent-up rage he radiates, there is an inevitability to him taking the law into his own hands, similar to the underbelly of evil that still resided in Eastwood’s “retired” hitman character, Will Munny, in Unforgiven. Dave Boyle (Tim Robbins) is emotionally tortured after being sexually abused as a kid. The actual law enforcement officer of the three, Sean Devine (Kevin Bacon), is equally cynical about the world and dubious of his ability to serve justice. After a traumatic event the three experienced as youths, they view the world as cold, bleak, and lawless. Eastwood’s direction and striking utilization of Boston as a character morph the entire story as a modern spin on Western themes. Characters intersect regarding the murder and the ensuing criminal investigation and cannot fathom any solution. All they can do is vent their grief and sheer vengeance.

At the very least, Eastwood reveals untapped sides of his personality and creative sensibilities when removed from the prism of Westerns. Along with Dirty Harry in 1971, Eastwood and Don Siegel teamed up for The Beguiled, a gothic romance/thriller that spiced up the power dynamic of an Eastwood picture by submitting him to the will of obsessively romantic girls at a boarding school students. Speaking of romance, in a more wholesome turn but not any less emotionally punishing, Eastwood showed unprecedented nuance with his acting and directing in The Bridges of Madison County. While using his natural physical attraction to his benefit, this 1995 romance, starring alongside Meryl Streep, unveils his internal beauty. With its loose structure predicated on two star-crossed lovers vicariously forming a lifelong relationship in four days, the audience is left to merely be in awe of Eastwood’s romanticism. The shock of this ideal matinée idol being the same actor behind Dirty Harry complements the film’s dramatic weight. Eastwood’s contributions to the cultural formation of Westerns are the work of legends, but as both an actor and director, he pushed the limits of his persona and the form of the film medium when stepping away from the Western template. In short, this feature ought to serve as a proper reminder to not take Clint Eastwood and his vast accomplishments in the field for granted, because when he moves on, there will never be anyone else like him.