Hollywood and the downwinders still grapple with nuclear fallout

The US turned swathes of desert radioactive during the cold war and denied it, bequeathing a medical mystery that still haunts Hollywood and rural Mormon communities and raises the question: how much do you trust the government?

The photograph shows John Wayne with his two sons during a break in filming on the set of The Conqueror, a big budget blockbuster about Genghis Khan shot in the Utah desert in 1954. It was one of Hollywood’s most famous mis-castings. The duke could do many things but playing a 13th century Mongol warlord was not one of them. Film geeks consider it one of the great turkeys of Hollywood’s golden age.

There is another, darker reason it endures in film lore. The photograph hints at it. Wayne clutches a black metal box while another man appears to adjust the controls. Wayne’s two teenage sons, Patrick and Michael, gaze at it, clearly intrigued, perhaps a bit anxious. The actor himself appears relaxed, leaning on Patrick, his hat at a jaunty angle. The box, which rests on a patch of scrub, looks unremarkable. It is in fact a Geiger counter.

It is said to have crackled so loudly Wayne thought it was broken. Moving it to different clumps of rock and sand produced the same result. The star, by all accounts, shrugged it off. The government had detonated atomic bombs at a test site in Nevada but that was more than a hundred miles away. Officials said the canyons and dunes around St George, a remote, dusty town where the film was shooting, was completely safe.

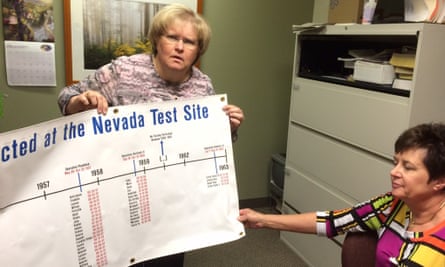

Last week, half a century later, Rebecca Barlow, a nurse practitioner at the Radiation Exposure Screening and Education Program (RESEP), which operates from the Dixie Regional Medical Center in St George, now a prosperous little city with an airport, leafed through her patient records. “More than 60% of this year’s patients are new,” she said. “Mostly breast and thyroid, also some leukaemia, colon, lung.”

This is a story about cancer. About how the United States turned swathes of the desert radioactive during the cold war and denied it, bequeathing a medical mystery which to this day haunts Hollywood and rural Mormon communities and raises a thorny question: how much should you trust the government?

“It’s gone into our DNA,” said Michelle Thomas, 63, an outspoken advocate for the so-called downwinders, the name given to the tens of thousands exposed to fallout. “I’ve lost count of the friends I’ve buried. I’m not patriotic. My government lied to me.”

Hollywood is set to remember its own cameo in the story with next year’s 50th anniversary of the release of The Conqueror, the film which allegedly killed Wayne plus leading lady Susan Hayward, director Dick Powell and dozens of other cast and crew members. In the meantime there will be another anniversary: this summer it will be 70 years since the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs.

The Manhattan Project scientists conducted the first atomic tests in great secrecy in 1945 in New Mexico. After the second world war, testing shifted to the southern Pacific Ocean on the grounds of public safety. But the war in Korea and escalating rivalry with the Soviet Union prompted a shift back to the US mainland for greater security. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), an agency with near Olympian powers which ran the nuclear programme, selected a government-owned bombing and gunnery range in Nevada partly because winds would blow “radiological hazards” away from Las Vegas and Los Angeles towards “virtually uninhabitable” land downwind to the west, home to ranches and Mormon communities.

From 1951 to 1962 the AEC detonated more than 100 bombs, sending huge pinkish plumes of radioactive dust across the stony valleys and canyons of southern Utah and northern Arizona. It gave each “shot” names like Annie, Eddie, Humboldt and Badger. The official advice: enjoy the show. “Your best action is not to be worried about fallout,” said an AEC booklet. Families and lovers would drive to vantage points for the spectacle, then drive home as ash wafted down on their communities. It was a cheap date.

At first the local press cheered the chance to beat the Russians and be part of history. “Spectacular Atomic Explosions Mean Progress in Defense, No Cause For Panic,” said an editorial in the The Deseret News. Clint Mosher, a columnist, said he never saw a prettier sight. “It was like a letter from home or the firm handshake of someone you admire and trust.’’

Seated in her home in St George last week, Claudia Peterson, 60, another downwinder advocate, gave a wry smile at the memory. “We were Mormons and very patriotic. Perfect guinea pigs. We weren’t going to question anything. It was impossible to believe our government would consider us expendable.” Peterson has lost a father, sister, daughter and nephew to diseases she attributes at least in part to radiation.

Eleven bombs were detonated in 1953, including several between March and June that coated St George and other towns in grey dust. The most notorious were a 51-kiloton shot called Simon and a 32-kiloton shot called Harry (later dubbed Dirty Harry). Thousands of sheep died. An AEC press release blamed “unprecedented cold weather”.

A year later St George’s 4,800 residents found themselves hosting an exotic invasion of actors, producers, technicians and stuntmen. Howard Hughes, the eccentric head of RKO Pictures, lavished money on what he envisaged as a stirring tale of romance and epic battles on Asia’s steppes. The cast and crew filled the motels and enlisted locals as labourers and extras. About 300 Shivwit Indians played Mongol villagers.

Dick Powell, the actor-turned-director, took the gig for the pay check, said his sonNorman, himself a director, speaking from his home near Hollywood. “He told me of these meetings in the middle of the night with Hughes and how weird it was.”

Norman, who accompanied his father and worked as a labourer and an extra, recalled hot, dusty weeks filming battle scenes in Snow Canyon, a wind-trap. Nobody worried about radiation. “There was no concern. None.”

It was an arduous shoot but left happy memories. “This is the way we like to think of America – people cheerfully helping people because that’s simply a good way to live,” Wayne recalled. The locals collected autographs and made good money. Everyone seemed to do well except the Shivwit, according to Rob Williams, a California writer who researched the film for a novel he is writing. “They were paid $2 or $3 a day and left to sit in the sun while the stars were in air-conditioned trailers.”

The film fared reasonably well at the box office, earning nearly $12m. But risible dialogue (“I feel this Tartar woman is for me, and my blood says, ‘take her’”) and the duke’s efforts to pass as Asian with a Fu Manchu moustache and furry cap convinced no one, least of all Wayne, who was quoted saying the moral was “not to make an ass of yourself trying to play parts you’re not suited for”. The film became a laughing stock.

And then, as years passed and cast and crew fell sick, it acquired a darker reputation. Powell got lymph cancer and died in 1963. “It got him pretty quickly,” said Norman. The same year Pedro Armendáriz, a Mexican actor who played Khan’s right-hand man, Jamuga, shot himself after being diagnosed with terminal cancer. Hayward, who played a Tartar princess, died of brain cancer in 1975.

By the time Wayne succumbed to stomach cancer in 1979, The Conqueror had been dubbed an RKO Radioactive Picture. His sons Patrick and Michael battled – and survived – their own cancer scares. Whether out of guilt or some other reason, Hughes bought up all the copies of The Conqueror and reputedly watched it every night in his final, reclusive years.

A People magazine article in 1980 reported that of 220 cast and crew, 91 had contracted cancer, with 46 of them dying. No bombs were tested during the filming, but the article quoted Robert Pendleton, director of radiological health at the University of Utah, saying radioactivity from previous blasts probably lodged in Snow Canyon. It also attributed an immortal quote to a scientist from the Pentagon’s defense nuclear agency: “Please, God, don’t let us have killed John Wayne”.

Did the US kill its own embodiment of grit and patriotism? The answer is: probably not. His chain-smoking of up to four packs of cigarettes a day was a likelier cause of death, according to his widow, Pilar. Many of the rest of The Conqueror’s cast and crew were also heavy smokers. Norman quit in his 20s and is today a vigorous 80-year-old who hikes and pumps iron. He thinks radiation was, at most, a contributory factor to his father’s death. Wherever it comes from, cancer haunts him. “My father, mother, youngest daughter and five of my closest friends died of cancer. I hate that fucking disease.”

The approximately 100,000 people who lived in the three-state fallout zone north and east of the testing site are more likely to have been affected than the Hollywood visitors. For years they inhaled contaminated dust and ingested contaminated food and milk. In the early 1960s, multiple cases of childhood leukaemia and adult cancers began to appear, a shocking novelty because Mormons, who shun alcohol and tobacco, typically have low cancer rates. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1984 compared those in the fallout area with other Mormons and found leukaemia levels five times higher.

Thomas was in her mother’s womb in 1951 when testing started. As a child she would duck under her desk during nuclear drills only to be sent out to play, she said, in a school yard coated with ash.

Her mother, Irma, waged a lonely campaign warning of the dangers. “She wrote letters and made a chart with rows of square boxes representing homes in our neighbourhood. Whenever someone got a disease she put a cross in the box.” As a cheerleader with beauty pageant ambitions, Thomas was embarrassed by this kooky-seeming activism – until she was stricken with polymyositis, a debilitating loss of muscle mass. Later, she got breast cancer. She survived, but her mother succumbed to cancer.

Speaking last week from a wheelchair in the yard of her St George home, Thomas was an acerbic, outspoken advocate for downwinders. “You have to forgive me if I don’t give a shit about John Wayne. They rewrote my DNA. They rewrote my life.”

Government scientists, drawing on data from Nagasaki and Hiroshima, used to visit schools to check thyroids and radioactivity levels, recalled Peterson, another advocate. “They wore black suits like the Blues Brothers. They knew what was happening.”

Above-ground testing paused in 1959 and briefly resumed in 1962, after which it went underground, where hundreds more bombs were detonated (including some on behalf of Britain’s nuclear programme) until a moratorium in 1992.

Government denials about any cancer-causing fallout unravelled in the 1980s, when lawsuits uncovered internal AEC reports showing scientists and bureaucrats downplayed and distorted evidence. Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act in 1990, establishing a fund for downwinders with cancer and serious illnesses apparently linked to above-ground nuclear weapons testing. Compensation is capped at $50,000 per person.

The fund has disbursed about $2bn and is set to continue until first-generation downwinders have died out. Their children and grandchildren, regardless of any health problems, are excluded. The Radiation Exposure Screening and Education Program (RESEP) has eight clinics in the region. They diagnose and advise about treatment, which is free if you qualify.

The clinic in St George, a bright, modern facility, has received an average of 140 new patients every year for the past five years. Barlow, the nurse practitioner, and Carolyn Rasmussen, a counsellor and case manager, hear recollections of watching sunburst explosions, sweeping ash from porches and watching relatives die.

“Listening is part of the job,” said Rasmussen. “Some people are grateful we’re here, others are just angry and resentful about what happened,” Barlow said, nodding. “Some won’t take the money because they think it’s blood money. We tell them the government that created this programme is different from the government that did the testing.”

Multiple factors cause cancer and we will never know if radiation contributed to John Wayne’s death. But there is no doubt the atmospheric nuclear testing programme wrought a terrible toll on many families. Peterson, the activist who has lost multiple relatives, had an epiphany when she visited bereaved families in Kazakhstan, where the Soviet Union did its own testing. “I was afraid of these people my whole childhood and then discovered they weren’t monsters. It was our own governments that were killing us.”